The fundamental question, how much is that puppy in the window? We’ve covered how to understand what pre and post-money valuations are. So the next valuation question, why is the pre/post-money valuation so high/low? There are as many ways to value a business as there are stars in sky, and not all have much rhyme or reason (e.g. why is Snapchat worth $3 billion? I have no idea…).

Let’s start this discussion with the basic valuation technique, known as the discounted cash flow model. In order to value a business, we look at the future cash flows from a business and apply a discount to those future cash flows, until we end with one number (called the net present value). We can get very technical very quick with some nice models, since most stocks are valued this way. But, venture businesses are not so I’ll save the models for later.

Venture businesses are not valued based on the discounted cash flow model because there are no future cash flows for a LONG time. A great success story for the venture community is Workday, which was founded in 2005 and generated positive cash flow for the first time last year. Pretty hard to value those cash flows almost nine years later. Venture businesses are usually valued on different sets of metrics, the most common of which is a multiple of revenue.

That math is easy. Let’s look at RingCentral (publicly traded – ticker RNG, but a still traded based on a multiple of revenue like a venture business). They generated $148.3 million of revenue over the past twelve months (a common term used for the last twelve months is the “trailing twelve months” or TTM), and have an enterprise value of $1.17 billion (enterprise value is a term to define the total worth of a company). This represents a multiple of 7.9x ($1.17B / $148.3M). Pretty simple right?

But how do venture funds decide what multiple of revenue to use? That is key question to almost every venture deal. Usually a VC will create a “comp set” (competitive set), consisting of businesses that are similar based on a few key aspects. Usually the business model is the first on the list.

A business model is the way in which a company generates revenue. An example: Netflix charges a monthly fee to its customers; this business model is called a subscription business model. But no one would think that Netflix and Workday belong in the same comp set – yet they do have the same subscription business model. That is why there is consideration given to the industry a business operates in, the type of customer, the geographic diversity, the technology platform, the growth rates, the gross margins, end user adoption, customer engagement rates, etc. There is no perfect mix, and it’s more of an art than a science.

You can also use a multiple of something other than revenue. Companies like Snapchat that don’t make any money still are valued based on a multiple. In Snapchat’s case, they are valued based on a multiple of their users. Foursquare, Twitter and Facebook were at one point all valued based on their users. Revenue multiples are just one of many options to set a valuation, but it is the most common.

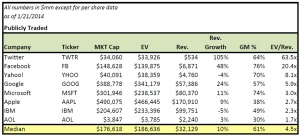

Putting this valuation technique to work, let’s go back to our Company XYZ. Company XYZ wants to raise money, and needs to set their pre-money valuation. If I were the CFO (conveniently in this example, I am!), I would start by creating a list of public and private companies that are similar to mine, and find a couple of multiples to value those businesses. If Company XYZ were a cloud company, I could use the Bessemer Venture Partner’s Cloud Comps median enterprise value (EV) to revenue multiple of 9.9x to set my valuation based on my 2013 revenue. If we generated $15 million in 2013 and grew at a strong rate, I would look to raise money with a pre-money valuation of $148.5 million (9.9 * 15M = 148.5M).

There it is. That puppy in the window costs $148.5M. Valuing a business that is losing money at very high rates is not easy, and tests the basic thesis of the discounted cash flow model. But when we find a common set of metrics to base that valuation on, you will see that it isn’t that extreme.

Just for reference, check out the EV/Rev multiples (enterprise value to revenue multiplies) of a bunch of well-known companies below: