One of the interesting trends we’ve seen in the markets over the past few years is the large premium paid in the public and private markets for recurring revenue business. Knowing that people are paying more for term, there has to be fundamental financial reason. There is.

Tldr (or for those unfamiliar with the internet – “Too long, didn’t read”)

The short answer: in a term business investors assume that the Company will generate more money over the lifetime of the customer by charging higher annual fees, rather than a large upfront payment and only a small recurring maintenance contract.

The long answer

As a reminder – a perpetual license means you pay once for the license and own it forever. Most enterprise licenses include a maintenance contract that entitles the owner to support and updates to the software as long as they own it, for approximately 20% of the total cost of the contract each year. A term license is the right to software for only a fixed term, in most cases a one or two year timeframe. Every year, the buyer has to pay the annual fee again, but constantly gets updates and support. Typically a term license is priced to be equal to a perpetual license over three years.

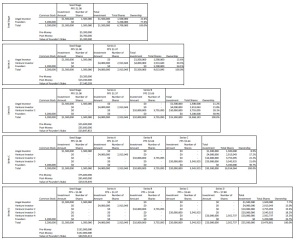

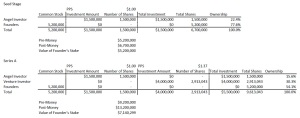

Here is an excel model that plays out those two business (Click here to download) – a perpetual business and a term business (download it and play with the assumptions by changing a blue cell). The total cost of ownership over three years is $1680 in both pricing scenarios (perpetual – $1200 year one, $240 year two, $240 year three; term – $560 per year).

I assume strong growth in both scenarios, with the same number of widgets sold each year. The trend you will see is that the recurring component of sales is much higher in the term business. By year 5, the Company is generating more money from existing customers than from new sales.

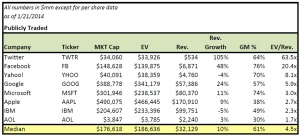

What is really interesting is when we look at the value of both business based on current public comps (I list the comps on the second tab that I used to find the median EV/TTM Rev). Applying the current market multiples to both business, you will see that in first few years, the enterprise value of the businesses are about equal, but in the last few years, the term business’s enterprise value is higher.

Summary

So what? Both business models have their benefits. Perpetual models generate cash much faster (most of the total value is paid in year one), while term licenses collect equally over three years. The key, is that in year 4 that term license is paying the same $560, while the perpetual deal would only get a maintenance payment of $240. Term is up $320 per license. As long as a customer pays for more than three years, a term model is better. That’s why people will pay more for the same business selling the exact same number of licenses in a recurring model.