So, we get it. Companies raise money, they need to set a valuation to raise said money, and they sell some of the business to raise that money (money, money, money). There are some important things to understand in the fundraising process, and there isn’t enough time to cover them all, so I’ll stay on the ones I think are important.

Signaling

Raising money is very much so a marketing move. There is (hopefully) positive press that can come from a capital raise. When you raise money and announce your valuation, that sets expectations in the market – namely it shows what investors think the business is worth today. It also figures into what investors think it COULD be worth in a few years. Venture investors target a 3x to 5x multiple of their money in any given investment. Generally, that means the business needs to sell for three times the amount of the last round. So, raising money at a $250mm valuation suggests that the business should be able to be sold for between $750mm and $1.25B. That is a lot of money.

In addition to the signal and expectations from a valuation, the existing investors’ involvement in each round matters. If a venture investor invested in the Series A and Series B rounds, but doesn’t invest in the Series C, it doesn’t look so good. It typically signals that the venture firm has less conviction in the future prospects of the business. Some seed funds and early stage investors will not typically continue investing for the entire lifecycle of the business, but usually investors continue to fund a business if they think it will be successful.

Pro-Rata

This concept of continuing to support a business is demonstrated in a cap table through pro-rata investments in subsequent rounds of financing. That is investor speak for putting up your fair share of the next round of equity. There are a few ways to calculate what “pro-rata” represents (either your share of a future round of investment or the amount required to maintain your ownership percentage in the business). There is a great post on Brad Feld’s blog here about pro-rata if you are interested. Not even all VCs agree on what “pro-rata” means…

Liquidation Preference

In a standard venture deal, there is a concept known as a liquidation preference (again, covered by Brad Feld well here). The liquidation preference is a set amount of capital that the preferred shareholders (venture investors receive preferred shares in a business with each investment) receive in preference (i.e. BEFORE) the common shareholders. Founders and employees of the business receive their shares in the form of common shares.

This means, when the business is sold, those investors will receive a set amount before the common shareholders. Typically, there is a 1x liquidation preference (meaning 1x the amount invested, so a $5mm capital raise will include a liquidation preference of $5mm). There are two ways to calculate what this means: Participating Preferred Shares and Non-Participating Preferred Shares.

Participation

Non-participating shares have a right to receive either their liquidation preference OR their fully diluted ownership percentage. Participating shares receive both their liquidation preference AND their fully diluted ownership percentage. Let’s use an example to show how this works.

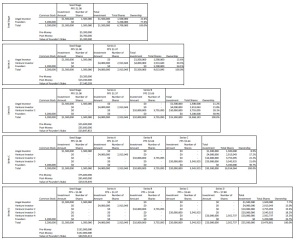

Assume that HotStartup raised one round of financing equal to $5mm at a post-money valuation of $20mm (meaning they received 25% of the business), with the founders retaining the remaining 75% of the business in the form of common shares. In any sale of the business for less than $5mm, if there is a liquidation preference – the preferred shareholders would receive all of the capital. If the business sells for more than $5mm, there are a few different outcomes.

If the shares are participating preferred shares, in a sale of HotStartup for $30mm, the investor would receive the first $5mm (their liquidation preference) AND 25% of the remaining $25mm ($6.25mm). The investor would return a total of $11.25mm, with the founder getting only $18.75mm.

If the shares are non-participating, the investor has the right to EITHER the liquidation preference OR their ownership percentage of the total sale. So in our last example, they would get EITHER their $5mm liquidation preference OR their 25% of the $30mm ($7.5mm). Obviously they would take the $7.5mm, leaving $22.5mm for the founders.

The difference between participation and non-participating shares is huge (in our simple example, the difference between $3.75mm!). Despite this, I have encountered countless management teams that do not know if the investor’s shares in their business are participating or non-participating. For reference, according to PitchBook, 60% of rounds in 2013 were non-participating, with 30% have uncapped participation and 10% have a cap on the participation (meaning a limit to the amount that the investor may receive both their liquidation preference and ownership percentage).

There are TONS of nuances within a term sheet, and I highly encourage every founder to have an experienced lawyer look through the terms of a deal on your behalf. There is too much that can be slipped into a term sheet and the legal documentation, all of which can have an enormous impact on the potential economics.

This was a long post, and was one of a three part trilogy (part one here, part two here). There is a lot involved in a capitalization table, and even more nuances in the legal documentation. There is no harm is asking for help, there are tons of resources, and lawyers are always available (at their normal billable hours…). Don’t sign a contract unless you know what it means, it could cost you literally millions of dollars.