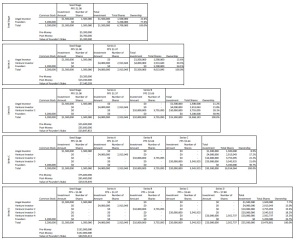

The second stage of the Cap Table Trilogy, The Empire Strikes Back (really no correlation to the Star Wars Trilogy, but I like Star Wars, so we’re sticking with it). At this point, HotStartup has built an amazing product, we’ve figured out our business model, and we are starting to really scale. $5.5mm has been invested by some great VCs and Seed investors. Time for that Series B.

Series B

This is the time to get some real money. We need bigger investors who are looking for the next three to five years, with some deep pockets. The investors skill set at this point isn’t focused on business models and early stage operations, but truly has a grasp on how to scale, and scale fast.

Thinking about HotStartup, we MAY have generated a couple million dollars of revenue in the last twelve months, but we are likely somewhere around that $5mm to $10mm range. In order to start really being interesting to a potential acquirer or to think about going public, we need to hit a minimum of $50mm. Growing by 10x in 5 years means we need to grow 59% annually – that’s a LOT. Big growth needs big dollars.

Valuation will also increase with this raise, and hopefully quite a bit. Thinking about the multiples, if we were able to generate somewhere around $5mm, a pre-money valuation of $25mm (5x revenue) would be fair. Including the $10mm ask, we would be at a $35mm post-money valuation (7x revenue), something that is within reason. This raise represents a 28% sale of the equity, and will dilute all the prior investors (remember, we assume no participation from old investors in new rounds).

Series C and Series D

Here is where things start to reach more normal, reasonable multiples for business. Things are based on the revenue of the business and the performance. We get a lower premium based on our potential, and a larger premium based on our business. Customers should be adopting the product, buying lots, and really NEEDING our product. Without HotStartup, the Fortune 500 would fall apart. We’ve spent $15.5mm on the product and are starting to scale at more than 50% annually. Let’s step on the accelerator, throw gas on the fire and really blow this out of the water (generic business terms always make you sound sophisticated, and are never a bad choice).

We need some serious cash to invest in the sales and marketing department (S&M). Research and development (R&D) are important, and should keep up with the innovation cycle in our business, but we already have a fully functioning product that is performing in the market. We won’t spend less on innovation, but we likely aren’t growing the R&D budget at 100% annually anymore (every busines is different, so I wont say that all business slow down their spend on R&D, just making an assumption from my experience). General and administrative (G&A) costs should start to be leveling out, as we should have a C-suite in place (or will have a C-suite in place post-Series C). We either retained the founder as CEO, or brought in a serial entrepreneur that knows the space; the CTO is one of the founders and is leading the product and innovation; a CFO is helping manage the equity partners, board members, banks, financial planning, audits (you know, the fun stuff!); and the COO is making sure the place isn’t falling down, keeping the business partners in-line and making sure our amazing product is always delivered the way it should be.

We’re investing to grow the business. Each dollar we invest will add to the growth of the business, and hopefully we can measure how this works. In a recurring revenue model there are lots of great financial metrics we can use to measure our performance (ARPU, AMPU, CAC, CLTV, Churn, etc.), making it easy to understand why investing $20mm of cash into a business that is spending $5mm to $10mm a year is totally logical. I promise venture investors are not dumb; there are always metrics that justify the investment.

So, what does this all mean for HotStartup? Well, we are going to need to balance our cash needs a little more carefully now. If we take a LOT of money in the Series C, we will be taking on dilution and cash at a time that we might be able to spend it as quickly as we would like. If we wait to take cash, we might miss an opportunity to grow the business at the exponential rate we need and wont maximize the value of the business. Here is where the financial expertise of a good CFO really matters, this is when we can start to really explore bank lines, venture debt, tranched equity raises, convertible equity notes, follow-on invetments, vendor financing, etc. For the purpose of understand how to build a cap table, I’ve put together some assumptions around valuations and capital raises based on the PitchBook VC fundraising report from Q4 2013 (embedded below as well). There are a TON of great insights in there regarding the valuations of business, investor rights, and standard terms. I encourage everyone who ever thinks about raising money to look in there and see what the REAL industry averages are for potentially expensive investment terms (which we will cover in the next section).

After all of the capital raised, and all of the money invested into the business – we as founders would own ~26% of HotStartup. That is really, really good. As one of two co-founders with 80% of that amount, we would have 10.6% of the business, worth $16mm at a $152mm post-money valuation. Not bad, but you know what’s really cool? A billion dollars (in my most sly JT as Sean Parker voice).