Preamble: Like all great Hollywood franchises, The Cap Table will be a trilogy. I can tell already, you are on the edge of your seat in suspense… There are a ton of valuable insights and important signaling events that a cap table represents, so I want to make sure I touch on everything appropriately.

The last couple of blogs have covered valuations and how we find them. Every time a company raising new capital it is setting a new valuation, selling a portion of the equity, and is re-establishing an exit target. There are reasons to raise new money, and there are costs and risks associated with each incremental raise that I will try to outline here. I’ll walk through the funding process from the perspective of new company – HotStartup. Without further ado, I present – A New Hope.

Friends and Family

When HotStartup is first starting out, it is just an idea in the back of our heads that will solve the Middle East conflict, eliminate starvation, and fix the healthcare system all in one shot. It’s a rocket ship and we know it will work. To get the first few dollars to build a prototype, get some first beta versions coded up and tested out we will use our own money, ask friends, family and anyone we know for some help. This is called a Friends and Family round, and really represents people putting money into the business based their relationship with you, and less about the actual business. Often this is in the form of a loan, credit cards, mortgage on a house, etc. Not really selling any equity, or if you are, it is part of the founder’s share of the business.

Angels / Seed Stage

But, since HotStartup is the best thing since, well ever, we see some great traction from our test customers and are starting to really refine the product. To get the whole thing working, we will try and raise $1,500,000 of capital in order to hire a few people and really build an enterprise ready product. At this stage, we are trying to raise an Seed Round, where either an institutional Angel group or seed stage investor will invest (such as Hub Angels or NextView Ventures) or even some privately wealthy individuals throughout our geography (such as high profile MA angles like Jonathan Kraft).

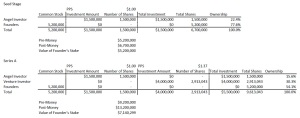

At this point, we need to start thinking about valuation and how much equity we are willing to part with. Since we don’t have sales or revenue to benchmark against, it is hard to know how much the business is worth. Often people will look at industry averages for a seed stage business, which the median pre-money valuation is currently is ~$5.2mm (mm = million, each “m” represents 1,000x, so $4m =$ 4,000, $4mm = $4,000,000). Since we have already covered pre-money valuations, we understand that our pre-money valuation of $5.2mm and a total equity raise of $1.5mm yields a post-money valuation of $6.7mm, and we are selling 22% ($1.5mm/$6.7mm = 22%).

Series A

We’ve got it! A full product, we’ve tested it out and people want to buy our HotStartup software. AWESOME!! This is fun. But, do we want to sell this as a perpetual license (think Microsoft Office, you sell a CD with everything on there, and people can use it for the rest of time), maybe a subscription license (where people pay us monthly/annually, like Netflix), or even a fully hosted SaaS solution (the newest trend is a SaaS offering, meaning we not only sell the product as a subscription, but also host it on our own servers). This process of figuring out the business model is when we go and raise a Series A round, with some really good venture capitalists that will help us think through things and guide us.

Again, it is a little early to really set the valuation based on our sales, but we aren’t just an idea anymore. Maybe we set things based some other user metrics or try to get a valuation of the business from a potential acquirer. For HotStartup, we will assume an industry average increase in the valuation of the business – a new pre-money valuation of $9.2mm and we can raise an additional $4mm cash (again, pre-money of $9.2mm plus the $4mm of equity raised yields a $13.2mm post-money, selling a 30% stake in the business)! This represents more dilution for us as founders, but also dilution from Angel investors.

Making it rain

Since we have some ideas of when, why and from whom we can raise money, let’s focus on some of the nuances of what this all means and how it impacts us. I’ve attached a breakdown of how the cap table would look if we raised new money from one investor at a time, with no participation from past investors. This is a simplification of the fundraising process, but helps to show how our founding stake in the business quickly goes from 100% to 54% after the Series A. After the Series A round, the implied value of our shares has been rising quite rapidly and is worth $7mm! So dilution means we get a smaller percentage of the company, but it is at a higher valuation.

In Part 2 we will cover financing through the end of venture (usually considered Series D), while finishing up in Part 3 with an analysis of some of terms in a venture contract (liquidation preferences, participation rights, drag along rights, anti-dilution clauses, etc.).